Spring 2024 Newsletter

How AMLT is Leveraging Maps and Spatial Science to Restore Ecosystems and Cultural Connections

By Annie Taylor, AMLT Consultant and PhD Candidate at UC Berkeley

The Amah Mutsun Land Trust (AMLT) has been doing groundbreaking work to map culturally important places and resources across the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band’s (AMTB) homelands for many years. As an environmental scientist specializing in mapping and spatial science, I was thrilled to get involved a few years ago to lead some of this work.

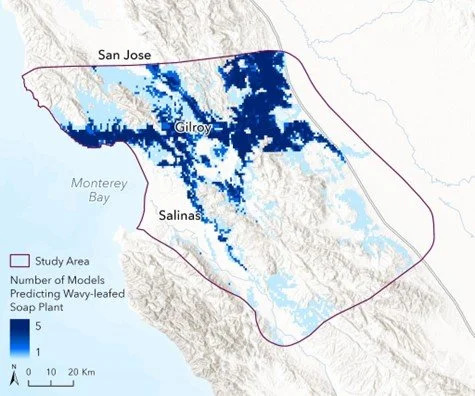

When I first started partnering with AMLT and AMTB, a number of wonderful people helped me get started with some existing projects to map culturally important plants. Sara French (AMLT) and the Native Stewardship Corps had collected lots of spatial information regarding culturally important plants, including where they were found, how abundant they were, and which seasonal stage they were in (e.g. if they were flowering or fruiting). From this dataset, we created heat maps showing where many different species of cultural plants were found within local open space preserves. Next, I modeled the habitat of ten different culturally important plants across AMLT’s entire stewardship area. As an example, a map showing the suitable habitat for wavy-leafed soap plant is below! Put together, the Tribe now has a (confidential) map showing dozens of potential hot spots for gathering cultural plants. I’ve also automated this workflow so that we can create potential habitat maps for many more cultural plants at the drop of a hat. This step is only the beginning – these maps will help AMLT and the Tribe decide how and where to partner with different landowners to steward and care for these potential gathering areas.

Map showing the probability of wavy-leafed soap plant habitat based on plant location data from AMLT and iNaturalist. You can read more about this work in this research article, co-authored by a tribal member: https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.4374.

My next and personal favorite project was to help map culturally significant sites across the landscape. Ed Ketchum, the Tribe’s historian, gave a presentation about many places that are sacred to the Tribe and the stories and knowledge associated with them. We transformed these presentations into digital maps and kept the rich stories associated with each site. While this was significant in itself, the Tribe didn’t stop there! In a radical step of reclamation, the Tribe purchased all of the state’s archaeological and cultural resource records within their stewardship area (these are known as CHRIS, or the California Historical Resources Information System). What makes this project so special is that the Tribe has reclaimed information that researchers and agencies have collected about their Mutsun cultural history and ancestors. AMLT and the Tribe now use this invaluable information to consult more holistically on potential development projects and prioritize certain areas for greater cultural protection. Maps hold immense power and more and more tribes are working to reclaim their own cultural resource data.

Our work to map the Amah Mutsun’s sacred sites is having a large impact outside the Tribe as well. In the case of Juristac, a sacred site along the Pajaro River east of Watsonville, maps are helping to communicate to legislators and the public about the sacredness of the landscape and where the threat of development sits in relation to it (see below). Maps are a critical communication and advocacy tool.

A map showing the Juristac cultural landscape with the current proposed developments overlaid on top. AMTB is leading efforts to stop the development of this mine. For more information, visit www.protectjuristac.org.

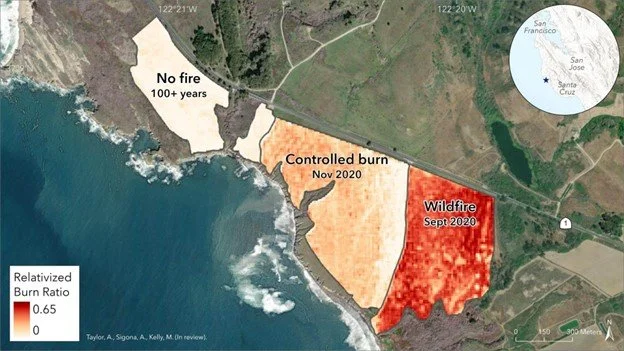

Lastly, we’ve been using satellite imagery to track the impacts of fire on a coastal grassland near Año Nuevo State Park – just across the street from the great restoration work happening at Quiroste Valley. Cultural fire is a sacred practice and a necessary stewardship strategy as the Central Coast contends with wildfires burning more frequently and at higher severity (to learn about Native Steward Esak Ordoñez’s recent experiences with cultural fire, click here). In addition, California’s endangered coastal grasslands rely on these frequent, low severity fires for growth and renewal. By studying this dynamic process both on the ground and from space, AMLT can monitor its effects and prioritize new areas for cultural burning. Here’s an example of that view from space – the image below shows how much more severe the CZU wildfire of August 2020 was as compared to a prescribed fire conducted in partnership with the Native Stewardship Corps in November 2020. We’re also using satellite imagery to track how these grasslands recover from this type of fire over many years, which helps to show the importance of the long term cultural fire stewardship that AMLT is working to restore.

Map showing the relative severity of the November 2020 controlled burn conducted with the Native Stewardship Corps as compared to an adjacent area burned in the CZU wildfire in September 2020, and a third area with no recorded fire in the last century. Darker red areas indicate a higher severity of burn.

AMLT continues to innovate and inspire in the realm of cultural and ecological restoration. Very soon we’ll be launching a current AMLT Stewardship Projects Map, which shows where AMLT’s many past, present, and future projects lie – so be sure to look out for that. I am deeply grateful to work with AMLT and the Tribe on these projects and I can’t wait to see what we do together next.